For decades, Jacksonville City Council redistricted based off ‘misinformation’

Analysis: The city is fighting a federal redistricting lawsuit by arguing the Jacksonville City Council was interested more in preserving historic districts. But a review of the history casts doubt on the legality of those historic districts.

Skyline view of Jacksonville with John Alsop Bridge. Visions of America/Joseph Sohm/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

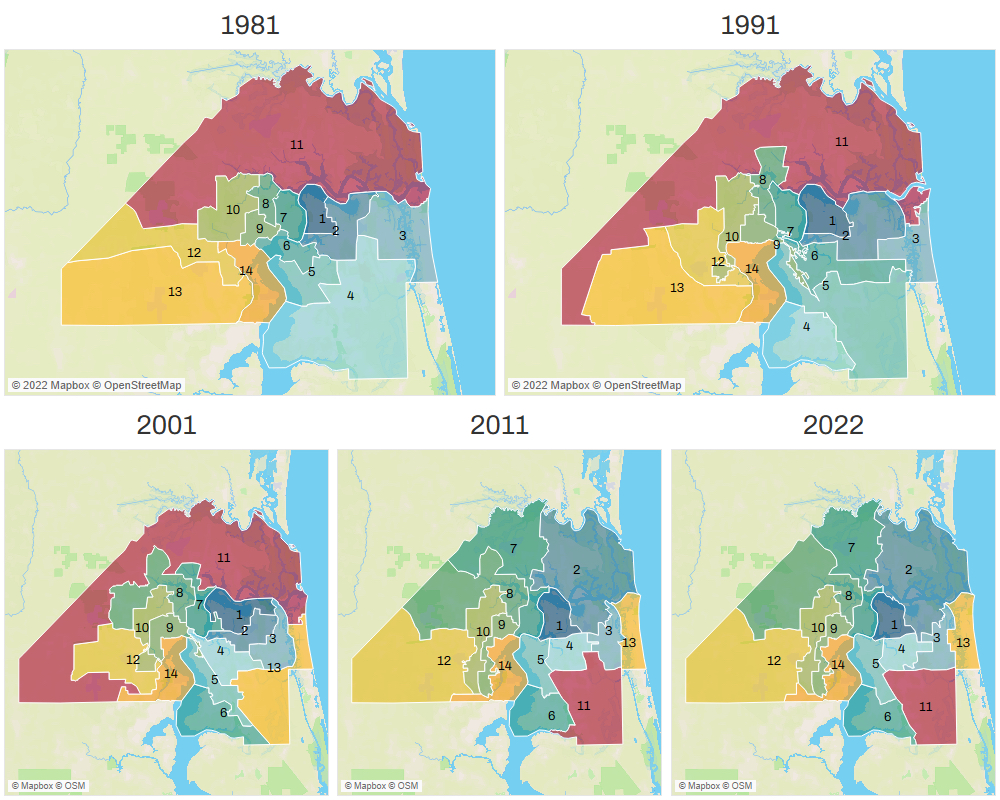

Misunderstood legal principles, incumbency protection and a willingness to ignore residents’ protests have driven the Jacksonville City Council redistricting for the last three decades. During that time, the council has packed as many Black voters as possible into four of the city’s 14 districts, apparently attempting to reach a mythical threshold based on a misreading of court rulings.

Doing so has meant reducing Black political power for decades, experts say. That historical legacy continued this cycle when two council members explicitly demanded city staff increase the Black share in their districts, even if it meant violating other principles.

The Jacksonville Branch of the NAACP and other civil-rights organizations argue in their federal lawsuit that the resulting map disenfranchises Black voters. The city responded by saying racial demographics didn’t drive redistricting. Instead, the City Council relied on other factors, the city argued, like “preserving prior districts and former constituencies.”

The Tributary dove into each of the past redistricting cycles to show how a misunderstanding about one Supreme Court case created a potentially illegal threshold that reduced Black voting power for decades in Jacksonville. This misunderstanding tainted redistricting for decades.

In September, a federal judge will hear arguments about whether to issue a preliminary injunction, likely based in part on whether the judge agrees the city did or didn’t allow race to become the predominant factor in redistricting. The City Council may continue to argue it was primarily trying to preserve old districts, but those old districts were borne themselves out of a desire to increase the share of Black voters as much as possible into four of the city’s 14 districts, a Tributary review of past redistricting cycles shows.

At times, the council did so even when it meant ignoring the protests of Black residents.

School Board member Warren Jones, who was a council member in the 1981, 1991 and 2011 redistricting cycles, said that he and the council were under the false impression that districts that protected Black voters’ ability to elect must be at least 60% Black.

“You really could reduce the Black percentage,” Jones said about the current districts. “The council, I think, is locked in now to not making any dramatic changes to the plan.”

The 60% threshold “was a benchmark set by the council members themselves,” said Property Appraiser Jerry Holland, who was involved in the 2001, 2011 and this most recent redistricting cycles. “That was a guaranteed number. You hit that, and you couldn’t lose as a minority representative in that district.”

John Libby, who now works at the county elections office, said he thinks he was the first to introduce the concept of a 60% threshold when he voluntarily drew the 1981 maps. Later, he tried unsuccessfully to persuade the council to abandon the quota.

“You were basing it off decades-old definitions that apparently were not true,” he told The Tributary. “… They kept going back to old [overturned] case law or no case law”

Matt Carlucci, who participated in redistricting in the 1991, 2001 and this most recent cycle, said he believes districts should be more integrated politically and racially. “I admit that in the past I have voted for redistricting that did not reflect the opinion I have now.”

He said that in past cycles, he knew of two rules of thumb: the 60% threshold and the need to maintain four districts that met that threshold.

“That led to some of the crazy lines we had, but it also led to peace in the community and council,” he said of the 2001 cycle he oversaw. “There’s a fine line you try to draw in order to be fair, keep peace in the family.”

At one point, the Department of Justice referred to the theory that threshold was necessary as ‘misinformation’.

When lawyers argue the most recent redistricting cycle was trying to preserve the status quo from the 2011 redistricting cycle, they’re pointing to a cycle where Jones and other council members explicitly said they wouldn’t accept a map unless it had four districts that were at least 60% Black.

CONSOLIDATION

When a local government task force first proposed Jacksonville consolidate with Duval County in the 1960s, it addressed redistricting and racial gerrymandering directly.

“Gerrymandering for purely selfish interests is exactly the kind of ‘politics’ at its worst that the study commission went to great lengths to avoid,” that task force’s executive director, Lex Hester, told journalists at the time.

The task force’s report proposed a form of government where voters could “pinpoint responsibility”. A nonpartisan planning board would redistrict the City Council and School Board. The City Council would have 21 districts, four of which would be majority Black, and the council would have no at-large members.

“Arbitrary lines”, the report said, were among the most important problems facing the city, alongside voter disenfranchisement and racial unrest. “District elections will assure equal representation for all parts of the County and will give particular population groupings a greater voice in the local government.”

Consolidation, everybody knew, would make the city’s demographics whiter and make it harder for Black voters to gain power in an at-large system. Black people made up 41% of Jacksonville residents but just 23% of Duval County. District elections would allow Black residents to still elect some of the new City Council members.

“We’ve been gerrymandered enough,” Alice Conway, a Black politician and activist, told reporters.

The Legislature changed the consolidation plans to a hybrid form of elected government, with 14 districts and five at-large seats. The non-political redistricting board — which Hester and others described as critical to keeping Good Ol’ Boy politicking out of City Hall — remained, but only for one cycle, handling the 1971 redistricting.

By 1981, the city had amended its charter so that City Council could draw its own lines.

A BRIGHT-LINE STANDARD

The mythology of a 60% or 65% threshold spread across the country in the 1970s and 1980s. A U.S. Supreme Court decision had upheld two New York districts in 1977 that used a 65% rule of thumb, but the opinion also specifically said there was no hard and fast rule and that redistricting bodies must find out what percentage is “necessary … to ensure the opportunity for the election of a Black representative.”

The courts never actually required a 60% or 65% threshold, said Jim Blacksher, an Alabama civil-rights attorney who has handled voting-rights cases since the 1970s. “White politicians who are in power and who want to cabin the Black vote in as few districts as possible may still rely on this old rule of thumb to justify doing it, but there’s no legal basis for doing it.”

That threshold became a bright-line standard over the decades of Jacksonville’s City Council redistricting. Using the threshold prevented Black voters from having any influence in the city’s other 10 council districts, limiting the influence Black residents could have in city politics. Courts have struck down maps that illegally used such thresholds without having a rational basis for doing so.

In 1981, after the council chose Libby’s map, he publicized the fact he had managed to get three of the districts above 65% Black and a fourth at 57% Black.

In 1991, the City Council hired former Florida House Speaker Jon Mills’ consulting firm. The firm called its plan the “63% Plan”, and the ordinance read: “It is the intent of the Council to provide four minority access districts with approximately 60% minority voting age population to meet the legal definition of fair opportunity.”

In 2001, The Florida Times-Union included a line in multiple stories that said “a district must be 60 to 65 percent black to have a high likelihood of electing a black representative.” It’s not clear if that information came from city lawyers or somewhere else. Yet three months before the first time it said this, the paper published a separate story about congressional redistricting that acknowledged protected districts did “not need to have a majority of minority voters” to allow Black candidates a fair opportunity.

And in 2011, council members and city staff obsessed over this 60% threshold.

“Percentages are driving the creation of the map, which is causing unnecessary shifts in the districts,” then-Councilman Reggie Brown said in one meeting according to the meeting minutes.

“Do not get hung up on the shape of the district,” then-Supervisor of Elections Holland responded, “as long as one is able to acquire the communities of interests and the numbers one wants. Set a benchmark to get as close to the numbers as you can.”

Holland told the committee he could draw a map with three 60%+ Black districts and one 59% Black district.

Then-Assistant General Counsel Jason Gabriel frequently interjected to say they couldn’t make race the predominant factor, but council members were undeterred. In one meeting, then-Councilwoman Denise Lee responded to Gabriel by saying they needed to “address minorities’ access.”

THE EIGHTIES

Drama filled the 1981 cycle. The City Council had tasked the city’s new planning director with drawing maps, but the director, who didn’t have redistricting experience, said it was impossible to draw maps with roughly equal populations. The mayor vowed to veto the maps.

Libby had seen in a newspaper story that the council had reached an impasse. “I said, I can do this,” he told The Tributary. “I went to the Haydon Burns Library and did some research. Here’s this court case saying how you have to do it” with 65% Black districts. “Literally, like I said, I went down to the main library and dug.”

The districts were more compact, the population disparities slight and three of the districts met the 65% standard, even though state legislative elections showed voters electing Black candidates in Jacksonville districts with smaller Black populations.

Voters elected Arnette Girardeau, a Black dentist, to the state Senate in 1982 in a 49% Black district. He won re-election twice. Then in the 1990s, Betty Holzendorf, a Black civil servant, held the seat against white opponents, even though less than 45% of the voting-age population was Black.

Jacksonville’s own federal judges ordered new maps in the 1980s in nearby communities to protect Black voters, and none of the maps packed as many Black people. A court-drawn Bradford County district was 53% Black. One in Live Oak was 52% Black. Another in Suwannee County was 56% Black.

In one case in the ‘80s, a Florida court issued an extraordinary correction because it had inaccurately referred to a 65% threshold. The Department of Justice called the court order “misinformation.” The amended order included a note that said, “There is no 65 percent threshold population figure applied as a rule of thumb by the Department in redistricting matters…. Rather, our responsibility is to determine whether the number of districts in which minority voters will have a fair opportunity for electing representatives of their choice (whatever the percentage of minority voters in each district).”

The department said it issued its note to “ensure that the error … is not perpetuated.”

But no one told the Jacksonville City Council.

1991

By 1991, when Jones served as Council president, the Council continued to insist on its threshold. Ginny Myrick, a then-councilwoman, asked Mills, the consultant, if it was possible to pass a plan that had 60% Black districts instead of 63% Black. “They are literally strafing my district to … to make the numbers that are valid in court,” she said at the time.

Another councilman called it “judicialmandering” because, he said, the court was making them do it. (In fact, no court had required the city adhere to the threshold.)

Mills and his fellow consultants later wrote a book about redistricting where they said the city had decided to use a “better safe than sorry strategy” and acted as if the city’s Black-majority districts needed to maintain roughly the same demographics even though the law didn’t require it.

They even admitted that Black residents “protested vigorously” their plan to make the Black-majority districts cross the river and connect Northside and Westside neighborhoods with Southside ones. Yet that plan still went into effect.

“Public hearings may be little more than window dressing,” they wrote in another section. “In fact, of course, the public contributes little.”

Mills and his fellow consultants described “irregular” districts that split neighborhoods and divided communities of interest. Four sprawling districts crossed the St. Johns River. One went all the way from Mayport and Atlantic Beach to Baldwin and the Clay County line.

2001

Ten years later, the City Council hired a local mapping consultant. This time, the consultant kept providing maps where the Black districts were lower than 60% Black, but the council and then-Mayor John Delaney rejected the plans.

“They’re just going to have to go back to their calculators and computers,” Delaney said then of the consultants.

“If we can get them [the percentages] higher in the white districts, we can get them higher in the black districts,” then-Councilwoman Pat Lockett-Felder said at the time.

Each proposal increased the Black percentages in the four districts, until the remaining 10 districts had been made as white as possible.

“As a councilmember in 2000, we thought you had to have them,” Holland told The Tributary about the 60% threshold. “It wasn’t just a desire. It was our mind that … in 2000 that was just the way it was.”

Then-Councilman Jim Overton pushed to keep Riverside, Avondale and Murray Hill together in one of the Black-majority districts. The Times-Union reported that move would have dropped the black population in the district from 58% to 51. The councilman who represented the district, Reggie Fullwood, rejected the proposal, saying it “disregard[ed] the need for minority-access districts.”

The newspaper reported on the proposal by again claiming without a citation that courts required the district to be 60% Black.

Eventually, Murray Hill was split mostly along racial lines. The whiter portions of the neighborhood were connected to Riverside and Avondale in one district while the portions with more Black residents remained in a separate district.

That split has persisted to this day.

2011

Ten years ago, the City Council committed itself to making the Southside districts more compact.

But the same commitment didn’t spread to the Northside and Westside, where the council’s Black-majority districts were located. Instead, city staff looked to pack as many Black residents as possible into those four districts, which also increased the white population as much as possible in the neighboring three districts.

“Neighborhoods represent the best community of interest and shouldn’t be divided,” said Terry Jones, one of dozens of activists who spoke out against the maps.

Libby showed up with his own proposal. He said an analysis would show a district that is at least 45% Black would be sufficient. (Later, when courts redrew one of the city’s congressional districts, it accepted a 45% Black district as sufficient, confirming Libby’s analysis.) Libby’s proposal also would’ve made the districts more compact, he said, and honored neighborhood lines.

At one meeting, two people told the council the 60% threshold was wrong. One woman, a former Black Republican councilwoman, said she had contacted the NAACP and the Department of Justice. She “stated that she took a group of interested citizens on a ride-around of her area and you can hit four council districts within the space of less than a mile,” the minutes from one meeting read. “… Minority access means 50% plus 1, not the 60% or 70% minority population the proposed districts seem to be designed to achieve.”

The council rejected Libby’s proposal and a separate proposal from Matt Schellenberg, a white councilman representing Mandarin, who had criticized the neighborhood splits and lack of compactness in the preferred map. He pointed out his map better complied with all of the council’s official criteria it had agreed on. But Jones criticized the plan for prioritizing compactness over race.

One councilwoman said she didn’t believe the neighborhood activists who favored Schellenberg’s plan accurately represented the opinions of other members of her community.

The council instead approved a map where the four districts ranged from 59% to 69% Black.

2021

This most recent cycle, no one discussed an explicit 60% quota in this cycle, but Councilwoman Pitman and Councilman Gaffney both pushed to increase the Black share of their districts as much as possible. Gaffney meticulously went through every census block on his district’s border to pick the ones with the highest possible Black populations.

And Councilman Garrett Dennis and Councilwoman Brenda Priestly Jackson rejected any efforts to change their districts, saying they were comfortable with the demographics in their seats.

As a result, their four districts ranged from 61% to 70% Black.

The council agreed on a set of non-racial criteria: protecting incumbents, drawing compact districts, honoring communities of interest, not crossing the St. Johns River and making as few changes as possible to the 2021 map. But those criteria didn’t end up factoring in much.

The council and its redistricting consultant later said before its final vote that incumbency didn’t play any factor for any of the districts. (Yet city lawyers argued in court the council prioritized protecting incumbency over race.)

The council also said that partisanship didn’t play a factor. At one point, redistricting committee chairman Aaron Bowman told The Tributary, “We didn’t look at party. … We looked at population data, and I don’t think that it would be appropriate for us to base our decisions on party.” (The city lawyers argued that the council prioritized partisanship over race.)

The map also split 47 recognized neighborhoods, and one district unnecessarily crossed the St. Johns River. (The city lawyers say that the council prioritized honoring communities of interest and major geographic boundaries ahead of racial considerations.)

Council members also rejected proposals that would’ve made fewer changes to the 2011 maps than the ones they eventually adopted. The reason: those proposed changes would’ve reduced the Black population in District 8, the district with the most Black residents. (The city lawyers say that the council prioritized maintaining the status quo districts ahead of racial considerations.)

The city also never conducted any analysis to determine how to protect Black voters’ ability to elect their preferred candidate, something experts and even city lawyers said was necessary to comply with the Voting Rights Act. Activists ended up hiring an academic to do the analysis for the city, but the City Council ignored the report, which said a 41% to 44% threshold would be more appropriate. (The city lawyers say the council prioritized complying with the Voting Rights Act above any other improper consideration of race.)

Neighbors and activists have threatened to sue the city over racial gerrymandering claims every decade but never followed through. Now they have, and a court will decide if the map unconstitutionally disenfranchises Black voters.

Plaintiffs must file a motion for a preliminary injunction by Friday, and the city will reply to it next month. The court will hold a hearing in September, at which point the judge will decide whether to toss Jacksonville’s redistricting map ahead of the March 2023 elections.

U.S. District Judge Marcia Morales Howard will decide if race improperly predominated in the City Council’s redistricting. If the districts are thrown out, Howard could give the City Council a second chance at drawing the lines.

While some council members told The Tributary they’d rather let the court take over drawing new lines if that happens, others said the council should get a second chance and should get enough time to ask for public input.

Regardless of how the court rules, Carlucci, who still serves on the City Council, said that the redistricting process needs to change.

“Redistricting on every level is one of the causes for our deep partisanship,” he said.

—

This story was originally published by The Tributary.

Andrew Pantazi edits and reports for The Tributary. He previously worked as a reporter at The Florida Times-Union where he helped organize the newsroom's union with the NewsGuild-CWA. He and his wife, Lauren, are both Jacksonville natives raising their two sons in the city. You can contact him at Andrew.Pantazi@JaxTrib.org.

NEXT STORY: Florida election preview: Eight congressional primary races to watch in 2022